In Episode 64 of the video lesson series, Uncle Bob introduces us to three foundational programming paradigms: structured, object-oriented, and functional programming. That episode maps to Part II of Clean Architecture book.

What is a programming paradigm?

A concept of “programming paradigm” is rather vague, and it seems to be dependent on what aspects the user of this term wants to emphasize. For example, one can talk about “imperative vs declarative”, or “procedural vs object-oriented”, or “parallel vs sequential” paradigms, or whatever else. All in all, the introduction of “programming paradigms” seems to attempt to classify programming practices by their features, and it depends a lot on what subset of features we want to focus on, and which ones to exclude.

I think Uncle Bob takes a similar path. Since his focus is on software architecture, he looks at programming paradigms as disciplines that we impose on the way we create programs. Having binary machine code at one extreme, as “wild West” of the programming freedom, where a programmer can do whatever she wants, he argues that programming paradigms don’t add capabilities. Rather, they remove capabilities from a programmer by imposing strict rules on what can’t be done.

I suspect also, that he focuses on the paradigms that lay down a foundation for future chapters, therefore he only chooses 3 paradigms that he thinks are most significant for software architects: structured, object-oriented, and functional programming.

The order in which he considers the paradigms is also somewhat arbitrary. From his narrative, one could imagine that they were discovered in that order: first structured, then object-oriented, then functional. The reality, however, is a lot messier. All these paradigms were discovered almost at the same time, with functional programming maybe even being the first: LISP was specified in 1958, while Dijkstra’s “GOTO Considered Harmful” (structured programming) letter came out a decade later in 1968. Object-oriented programming, attributed to Simula language, was conceived in 1962.

On the other hand, if we put the paradigms in the sequence of mainstream adoption, then they go in the order introduced in the book, so let’s stick with the narrative Uncle Bob suggests. It’s not a history book, after all.

Paradigms are ways of programming, relatively unrelated to languages. A paradigm tells you which programming structures to use, and when to use them.

Overall, the entire episode is summarized in the following sentence:

Well architected software systems are composed of recursive applications of sequence, selection, and iteration, hung on a framework of inverted dependencies and plumbed through and through with flows of immutable data.

Structured Programming

Structured programming imposes discipline on direct transfer of control.

In a nutshell, structured programming enables modular software. By prohibiting uncontrolled jumps between arbitrary places in the code, it allows developers to set boundaries between different parts of the code and give them total control over where the flow can cross these boundaries, e.g. function entry points.

It also emphasizes the recursive structure of software. The software is composed of modules, which in turn are composed of finer grained modules, and so deeper and deeper down. The flow of control between the modules on every level is done in the same manner and by the same means: sequence, selection, and iteration. In some sense, it enables the abstraction of complexity, where you can reason about the behavior of a system on a high level regardless of how the low level details are implemented.

Object-Oriented Programming

Object-oriented programming imposes discipline on indirect transfer of control.

The most important aspect of object-oriented programming is polymorphism. Although it it possible to obtain polymorphic behavior in languages like C with the use of function pointers, object-oriented languages made it safe and easy. Polymorphism is an important mechanism for software architects, because it decouples source code dependencies from control flow dependencies.

Before OO, the flow of control dictated the dependencies between modules on a source code level. With the addition of cheap and easy polymorphism, it’s no longer the case, and the architects gained absolute control over source code dependencies. This mechanism is called Dependency Inversion and it deserves a deeper discussion.

Dependency Inversion

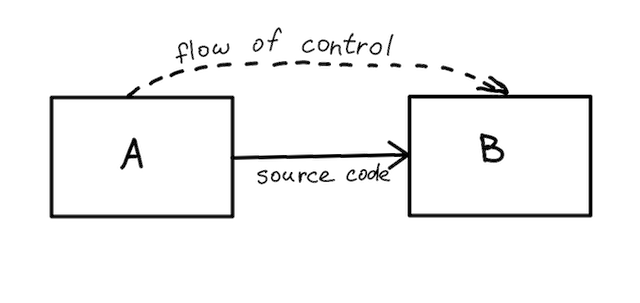

Let’s take a look at the following example. Module A is using the functionality from module B. Therefore, A depends on B at runtime in order to pass the control to B when the program is running. But also, module A has an explicit source code dependency on B, for example by use of Java’s import statement. The source code dependency implies that both A and B must be present at compile time, which makes their independent development or deployment virtually impossible.

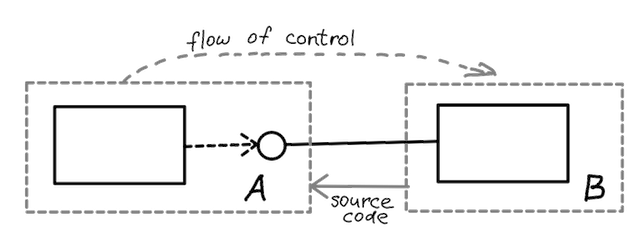

Now let’s consider a different code structure. Module A defines an interface it expects from B, and the source code in A depends solely on that interface definition. Module B, in its turn, still provides the actual functionality by implementing this interface. The overall functionality split between A and B is the same as in previous example, but let’s take a look at what happened to the dependencies between A and B.

The runtime dependency still hasn’t changed: A transfers the control to B. But the source code dependency is now going in the opposite direction! Module A now doesn’t need to know anything about B, but B is aware of A because it needs to import and implement the interface, declared in A. And that’s the dependency inversion at work.

The source control dependency is inverted relative to the flow of control.

We can take a small step further and extract the interface from A into a separate source code module, making both modules depend upon this shared module at the source code level. With that small change, A and B are now completely independent of each other on the source code level! This means that they can be developed and deployed absolutely independently.

In short, dependency inversion gives the software architect absolute control over source code dependencies, and enables independent deployability and independent developability of software modules.

Functional Programming

Functional programming imposes discipline upon assignment.

The biggest impact of functional programming is immutability. It favors immutable data structures, but mutable data (essentially, the assignment operator) is quite restricted. The importance of immutability is crucial for developing concurrent applications. Immutable data essentially eliminates problems inherent to concurrency: race conditions, deadlocks, and concurrent updates.

From the architect’s perspective, it makes sense to segregate the system along the lines of mutability into mutable and immutable components. You’d want immutable components to perform their tasks in purely functional way, free of concurrency problems. Mutable components, where data mutation is allowed, should take special precautions to avoid concurrency-induced problems, e.g. by the use of transactional memory.

As an architect, you’d want the majority of the code to be in the immutable components, and keep mutable components as slim as possible.

Event Sourcing

One technique Uncle Bob seems to be fascinated with is event sourcing. Event sourcing is a technique where the application state is stored not as its current value, but rather as a sequence of change events. The current value can then be calculated on demand by applying those recorded changes. For example, a bank account object would store all transactions that happened to it, and current balance would be calculated on the fly from them.

Event sourcing can be looked at as a functional approach to persistent data. Indeed, data becomes immutable: there are no updates or deletes, only creation of event records. That way, CRUD becomes simply “CR”. At the expense of stored data size and additional computation, event sourcing opens up new possibilities, such as:

- restore the application state at any point in time from the past;

- reverse the effects caused by incorrect events;

- reorder the events received in the wrong sequence.

One very common example of event sourcing implementation is a version control system.